The Special Intensive Revision (SIR) has drawn widespread criticism for its potential to disenfranchise eligible voters, particularly among marginalised, poor, and migrant populations. The short timeline, lack of public awareness, and reliance only on the 2003 roll raise concerns about administrative fairness and feasibility. Additionally, the process appears to shift the burden of proof from the state to the citizen, undermining the presumption of eligibility in a democratic process. Many view it as a de facto implementation of NRC through electoral means, lacking legislative backing, transparency, or adequate safeguards.

When the Constitution of India took steps to establish universal adult suffrage in India, it became the world's first large democracy to adopt universal adult suffrage from the beginning. It followed the model of instant adult suffrage, contrary to the common historical experience of ‘incremental suffrage,’ which means gradual expansion of voting rights over time. This model proved to be a nation-building and nation-preserving tool for India.

Article 326 of the Constitution of India guides that the elections to the House of People and the Legislative Assemblies of the state shall be based on Adult Suffrage. It means that every person who is a citizen of India, who is above 18 years of age and not disqualified under the constitution or any other law in force on grounds of non-residence, unsoundness of mind, crime or corrupt or illegal practice, shall be entitled to be registered as a voter in such election. The concept of adult suffrage in India has paved its way successfully to date from the point when some of the members of the drafting committee of the Constitution opposed it stating it is not theoretically and practically possible to implement.

Hence, the right to vote in India is a constitutional right, and the Election Commission of India, an autonomous constitutional body established under Article 324 of the Constitution of India, plays a pivotal role in safeguarding and administering this right.

The Election Commission of India is bound to play a vital role in ensuring free and fair elections. The roles cast on the election commission are to prepare and update electoral rolls, enforce the model code of conduct, monitor election expenditures, ensure law and order during elections and all the functions to supervise, direct and control the entire process of election. An Electoral roll/ voter list/ electoral register in this process is the official list of all eligible and registered voters within a specific constituency. The electoral roll is prepared and revised by the Election Commission of India under the Representation of People Act, 1950 and the Registration of Electoral Rules,1960. It is to ensure that the voter's list is accurate, inclusive and free from discrepancies over the period by allowing new registrations, deletions and modifications. It has been done since independence for various reasons like to improve accuracy, prevent ineligible entries and so on. Such revision may be intensive where the voters’ list is prepared from scratch by 100% door-to-door verification. It may be a summary revision or a special summary revision. Over the period we have shifted to summary revisions as they are cost-effective.

The Election Commission of India announced in June 2025 that it will begin a Special Intensive Revision of the electoral rolls in Bihar ahead of its state assembly elections and afterwards nationwide. This is the first intensive revision of the Bihar rolls since 2003. It aims for accurate and error-free elections based on factors such as urbanisation, frequent migration, the addition of newly eligible young voters, under-reporting of deaths and the inclusion of names of foreign illegal immigrants.

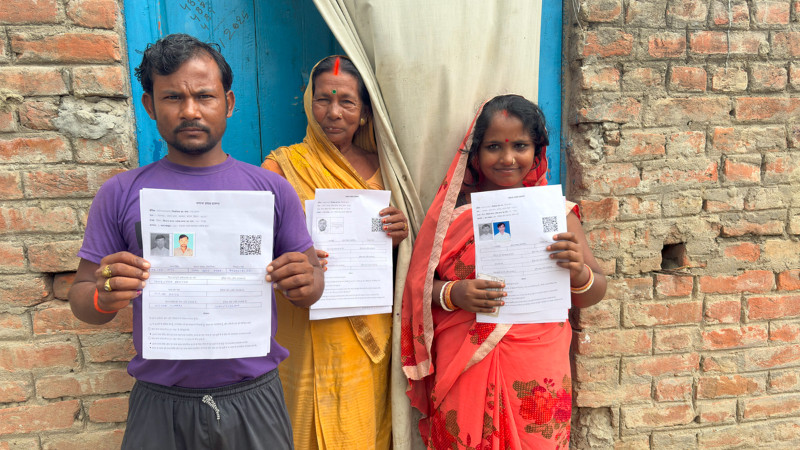

The process for this Special Intensive Revision to be conducted by ECI is the delegation of booth-level officers to conduct house-to-house verification. It will include a door-to-door survey to identify eligible and ineligible voters. All the voters have to fill up an enumeration form and submit it with the supporting documents as per their criteria. This process is also available through an online portal. However, the online process has multiple limitations like resources, education available as far as the marginalised sector of society is concerned.

The Election Commission of India has categorised the voters into three groups for the verification drive with each required to furnish a different set of documents. It is based on two years, 1987 and 2003 when India enacted the laws to prevent illegal immigrants from gaining citizenship that is The Citizenship Amendment Act, 1987and 2003. Those born before July 1, 1987, are most likely to be on the 2003 revised voter list. They only need to submit the enumeration form along with an extract of the 2003 roll, which has been made available online. However, those born before 1987 but missing from the 2003 roll are required to provide valid documents proving their citizenship and continuous residence to justify their inclusion. The 2003 voter list serves as the base document, and individuals on it as well as their children can use it to file the enumeration form. Voters born between July 1, 1987, and December 2, 2004, must submit one of 11 listed documents proving their date and place of birth, along with any such document for one parent. For those born after December 2, 2004, documents proving both their birth details and the citizenship of both parents are required. The voters have 30 days to provide evidence and another 30 days to contest if their names are deleted or wrongly entered into the database.

Even though the Special Intensive Revision is a constitutionally empowered mechanism, some incidents all over the world are unignorable when it was misused as a double-edged sword to influence electoral outcomes and systematically disenfranchise targeted groups. Some of the incidents of silencing the voters were during the mid-term elections of 2018 in the USA where Georgia’s ‘exact law’ disproportionately affected black and minority voters. Herein tens of thousands of voter registrations were kept on hold due to minor mismatches in voter data. Then one of the incidents of Rohingya exclusion in Myanmar. During the 2015 and 2020 elections, the Rohingya population was systematically excluded from the electoral rolls despite having voting rights in the earlier years. This demonstrated how ethnic or political motives can be masked under administrative actions such as voter verification or rolls revision.

In the Indian context, there have been incidents which resulted in the exclusion of legitimate voters. The National Register of Citizens (NRC) process in Assam so impacted the electoral rolls that it resulted in the exclusion of over 19 lakh people from the final list. The latest of all is the urban voter disenfranchisement in the state of Maharashtra, ahead of the 2019 Lok Sabha Elections where many urban voters in cities like Mumbai and Pune complained that their names were missing despite being registered in earlier elections.

Based on all these experiences the Special Intensive Revision (SIR) has drawn widespread criticism for its potential to disenfranchise eligible voters, particularly among marginalised, poor, and migrant populations. Critics argue that the documentation requirements, especially proof of birth and parentage are overly burdensome in a state like Bihar, where many citizens lack formal records and live outside their home constituencies. The short timeline, lack of public awareness, and reliance only on the 2003 roll raise concerns about administrative fairness and feasibility. Additionally, the process appears to shift the burden of proof from the state to the citizen, undermining the presumption of eligibility in a democratic process. Many view it as a de facto implementation of NRC through electoral means, lacking legislative backing, transparency, or adequate safeguards.

This Special Intensive Revision has been challenged before the Hon’ble Supreme Court in the case titled Association of Democratic Reforms Versus Election Commission of India. The petitioners argue that the Special Intensive Revision, especially its reliance on the 2003 electoral roll as a base, is arbitrary and exclusionary and violates fundamental rights guaranteed by Articles 14, 19, and 21 of the Constitution. The Hon’ble Supreme Court has refused to stay the Special Intensive Revision affirming that the Election Commission of India has the authority to conduct such revision. However, the court has directed the Election Commission to ensure that the commonly held identity documents such as Aadhar Card, Voter ID cards and Ration cards be included in the list of accepted proofs for verification. The court has also raised concerns over whether the process could be completed in the short time frame announced by September 2025 for Bihar state which has around 8 crore of voters.

Amidst the wave of criticisms and constitutional challenges directed at the Special Intensive Revision, the Election Commission of India has presented a reasoned defence of the exercise, asserting both its legality and necessity in ensuring the integrity of the electoral rolls. The commission has emphasised that the exercise is not linked to citizenship determination. The Election Commission of India has allowed the voters to submit the documents even at a later stage that is at the claim and objection phase if they fail to provide them at the initial verification. The voters have the right to raise claims and objections for which the proceeding is held before the Electoral Registration Officer (ERO). The person aggrieved by the decision of ERO can file an appeal before the District Election Officer.

While the Special Intensive Revision reflects a genuine attempt to clean and update electoral rolls, it must not come at the cost of excluding those who are already on the margins of society. Many citizens, especially migrants, the poor, and the elderly may struggle to produce documents or navigate the process within tight deadlines. The right to vote is not just a legal entitlement but a cornerstone of dignity and belonging in a democracy. To truly serve its purpose, the Special Intensive Revision must be carried out with care, compassion and inclusion. This can be done by accepting commonly held documents, offering flexible timelines, and ensuring no eligible voter is left unseen and unheard. A fair revision process is the one which strengthens both the system and the people it is meant to serve.

- Adv. Prachi Patil

pprachipatil19@gmail.com

(The writer is a practicing lawyer at the Pune District Court and the Family Court, Shivajinagar)

Tags: Bihar Assembly Elections Bihar Elections Bihar pecial Intensive Revision pecial Intensive Revision (SIR) SIR Voter Rolls National Register of Citizens NRC ECI Load More Tags

Add Comment