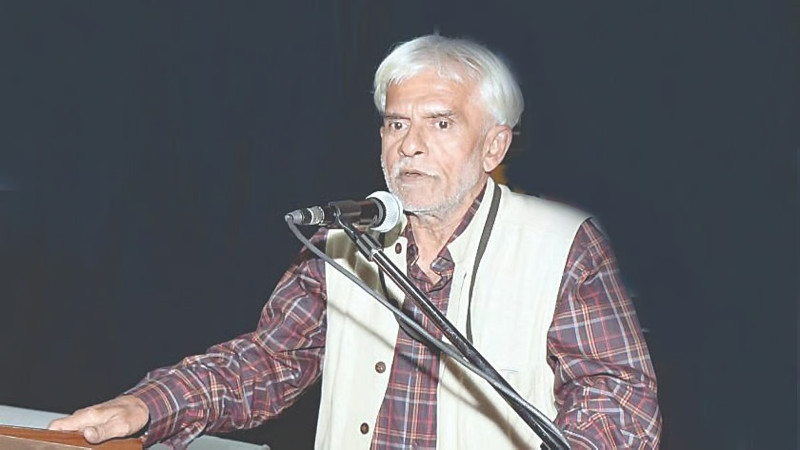

Dr. M S Swaminathan, a celebrated figure in Indian agriculture who recently passed away at the age of 98. Dr. Swaminathan's life journey, from a police officer to a renowned agro-scientist, is recognized. He is credited as a pivotal figure behind India's Green Revolution, which led the country to self-sufficiency in food production. Farmers are essential contributors to the nation's economy and their well-being should be prioritised. This article pays critical tribute to Dr. Swaminathan.

Dr. M S Swaminathan, the grand old maverick of India passed away at the grand old age of 98. Tears are uncalled for. Very few are able to fulfill the cherished dream of crossing 100. But accolades are in order and are flowing in; deservedly. Such was the mavericism of Swamy (my fond name for him) that he started as a police officer and ended up with the epithets of agro-scientist, agronomist, policy advisor, inspirer, motivator, administrator, institution builder: in short, but above all, the man who fathered the Green Revolution in Indian agriculture and enabled a scarcity haunted huge, third world country to achieve self-sufficiency in food. This achievement brought him fame in the country and over the world. The awards he received are a testimony to that: only the Nobel is conspicuous by absence: a case of exception proving the rule? But the praise he received from Norman Borlaug stands above all other honours: only Borlaug would know what tenacity and creativity was needed to the two successes.

I envy the generation of Swamy because they were on the launching pad at the time of Independence. For instance, Swamy was 22 in ’47 and when the Planning Commission was founded in 1952, he must have achieved some clarity about his role in the development of the motherland.

Shaping a development policy for a country of India’s size, geographical diversity, huge population divided by religion, caste, language and hierarchical social structure, essentially, is about doing the balancing act in a world plagued with contradictions: religiosity and secularism, tradition and modernity, fascination for dictatorship and democracy, patriarchy and gender equality, upper castes and OBCs plus the Dalit castes , obscurantism and rationalism, indigenous and foreign ,village-town and town-city to list but a few. Even in foreign policy in spite of the general unanimity, there are always anxieties over India getting too friendly with either block -capitalist and socialist (such as they are at present). The Constitution, which had been adopted in Swamy’s youth assured secularism, equality and self-fulfillment for all for a society which was the dream of sociologists but the nightmare of economists. Equality was still in future: masses were in the jaws of hunger, malnutrition, destitution and disease. In short, all-encompassing under-development was the ground reality. Swamy’s generation was blessed with this chance to convert calamity into opportunity: every qualified patriot could find a niche in this grand endeavour of building modern India.

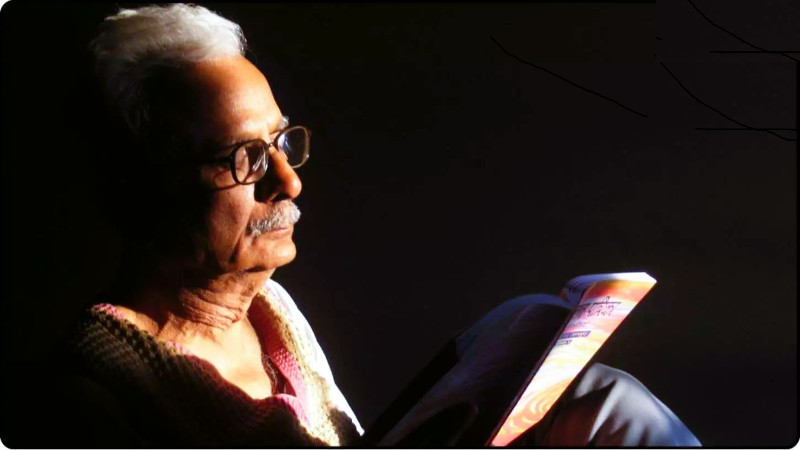

Later Swamy said in an interview that the Bengal famine of 1942 - which was both a man-made and nature-effected disaster and killed innumerable people - was a turning point in his youth as it opened his eyes to the poor productivity of India’s agriculture. He felt basic work needed to be done to increase the output. So, in the fifties he went abroad-where he met his life-partner too- and worked first on paddy improvement successfully. The keen observer that he was he realised that wheat was the other major staple of Indians and year after year the crop was getting destroyed as the Indian wheat shoots were too tall to sustain weight of the grains and fell flat-thus destroying the crop after it was ready to reap. His research drew his attention to the ‘Mexican Dwarf’, a shorter wheat variety and he developed an Indian seed that produced shorter shoots and helped it to stand erect till it was harvested.

Swaminathan examining chromosomes of irradiated cells under microscope

Swamy’s success on the productivity front was rightly lauded by all. Encouraged by the government, Indian farmers in Punjab, Haryana, Western Uttar Pradesh, and coastal Andhra Pradesh took to the new varieties in the 1960’s and by early seventies India ceased to be the world’s food beggar and was able to take bold steps in world affairs: the recognition of BanglaDesh, clean, successful Nuclear Test and the Friendship treaty with the Soviet Union. The relief from hunger surely paved a way to visualize a more dignified sovereignty for India.

But there was the other (dark) side to the Green Revolution which was evident in high indebtedness among farmers who had positively responded to the state initiative and implemented the policy drive for planting hybrid varieties. Their fields had turned green round the year yet whites of their eyes showed when they started getting loan repayment notices from the banks that had loaned funds which were essential for hybrid crops. The state had promised bijalee and pani -electricity and irrigation-and finance through banks. In fact, the State had promised everything except the what price the bumper harvests would fetch in the markets-both government run and private. So higher the yield, higher was the burden of loan on the producer. Banks which had been all smiles turned into Shakespearian ‘smiling villains’ when it came to recovery of loans.

Matters got worse when farmers turned to cash crops such as sugar cane and cotton because high yield varieties, especially of cotton, invited high spending on all items of input-seeds, fertilizers, irrigation pesticides et al. But procurement prices both by State and private traders remained stagnant. While the food grain farmers languished in debts of lower scale, the cash crop farmers found the burden unbearable. Sugar cane growers’ indebtedness became hereditary and suicides started in cotton farmers in Vidarbha and Andhra Pradesh in mid-1980’s: at the present date over 2.5 lakh farmers have ended their lives-it’s a sure possibility that the real number could be higher.

The moot question that needs to be asked is- no matter if only is retrospect- did Swamy see this side of the Green Revolution: plight of the farmers who accepted his scientific wisdom and went for the new varieties of paddy, wheat et al? To put in other words, did Swamy foresee this glaring contradiction that while India has long crossed the sufficiency bar in food grain, why there is such frustration among the farmers? Why, despite help packages and other welfare scheme farmers’ suicides do not stop? Why herds of farmers’ children are desperate to qualify for central and state government jobs instead of continuing in agriculture? Why some of the erstwhile non-backward proud farming castes are clamouring for reservations? Why even those with degrees in agriculture see government jobs as a better bargain?

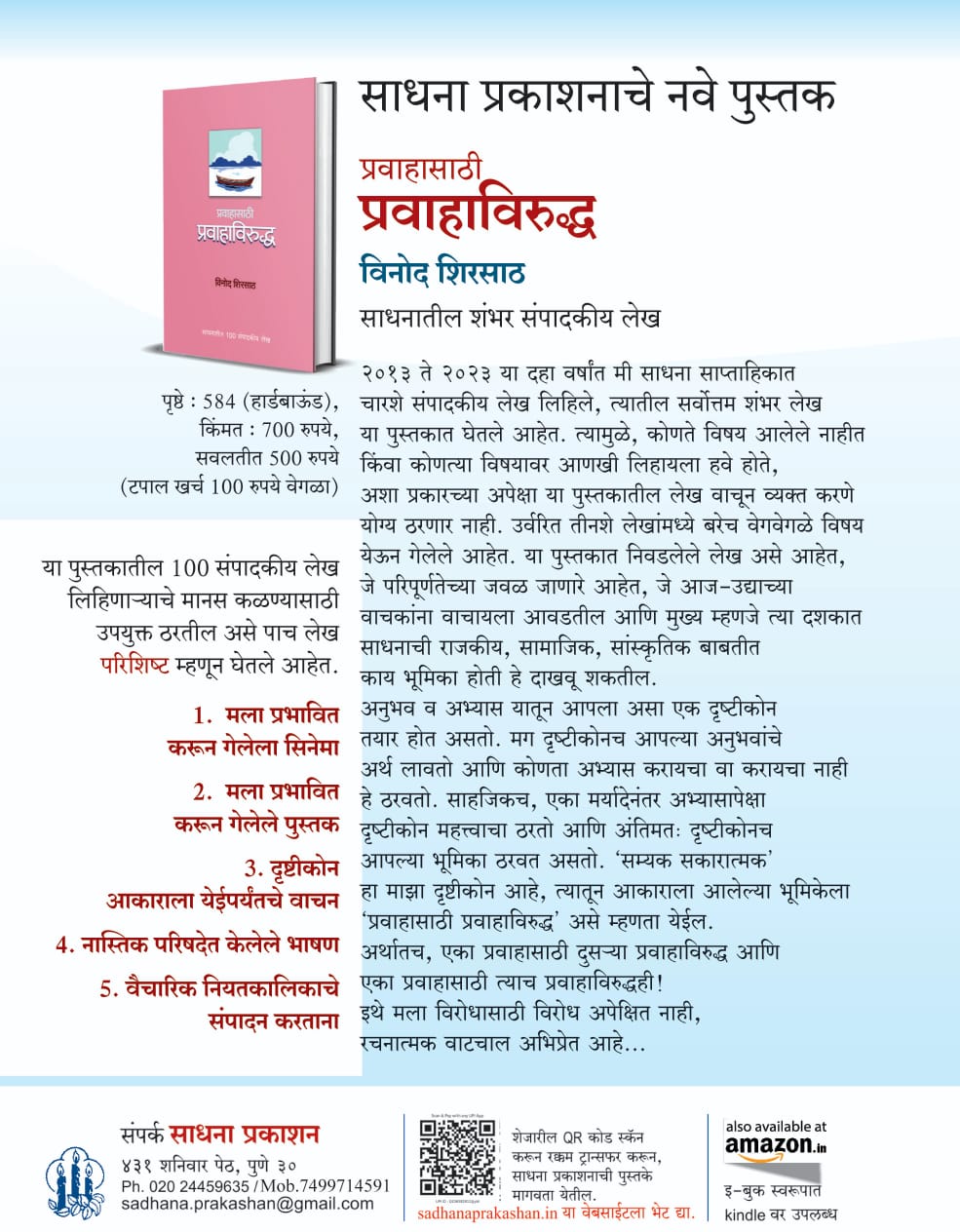

Swaminathan in wheat field with american agronomist Dr. Norman E Borlaug

Swamy is not to blame for this but it is impossible that this tragedy escaped him. There are three sides to this debate: Price, Infrastructure and Technology (knowledge and method). Swamy rightly belonged to the third-Technology and did his best there. The State provided Infrastructure at snail’s pace and its very presence created multiple opportunity for corruption in providing water, power, and roads to the farm zone all over the country. Traders extracted their pound of flesh in seeds, fertilizers, and pesticides. They also competed with the state in keeping prices low, creating short-supply scares and preventing export when the harvest was good: at times even goading the State to restrict movement of farm produce within the country.

By a rough estimate Indian farmers got Re 28 for produce worth Re 100 and the farm sector lost over 1.5 lakh crores annually till early 1990’s despite the two revolutions in agriculture: the Green and the White. That is why the share of agriculture has dropped below 20 per cent in GDP while over 50 percent of people still depend on it. Post Independence economic policy of India, one suspects, has treated the peasantry as just another item of input- with seeds, water, fertilizer etc.- and never looked at the farmer as an agent of economic development.

With the able and charismatic leadership of Sharad Joshi, Bhupinder Singh Mann and their colleagues from other states, the Shetkari Sanghatana in Maharashtra and the Bhartiya Kisan Union in Punjab and Haryana farmers got organized during 1980’s and put-up strong protests and agitations creating a joint front of the peasantry which was successful in taking the farmers’ issues to the top of political agenda in the country. But they failed, willy-nilly, to create a viable alternative to the political establishment. While all parties agreed to better the lot of the farmers, policies remained stagnant, or changed only cosmetically and were implemented without commitment.

Read Also : Monsoon Forecast: Yearly Fiasco - Vinay Hardikar

Swamy did see the other side of the Green Revolution-especially the urgency of compensating the farmers on the Price front when he recommended in a report to the Centre in 2007 that the procurement price should be fixed with a profit of 50 per cent on the cost of production and the sugar sector should be free of all State regulation. But it was an abysmally late admission: a lot of time, labour, lives, and wealth had been lost during the four decades since the advent of the Green Revolution.

The ITP debate is still relevant because there is no way out with emphasis on just one aspect: Technology (knowledge base) should be the starting point; Infrastructure should be the catalyst and Price-based on rational and real cost figures- should be the end. The farmers of the country are no lazy bones: their very survival despite such apathy shows that. Their wisdom and toil should be adequately rewarded. They should be looked upon as key players in the country’s economy and not as hapless countrymen who need to be helped by sops, subsidies and essential commodities at lower prices.

So I pay my deep respects to Swamy for his stellar work in agricultural research and join all in hailing it as agriculture-friendly, science-friendly, environment friendly, consumer friendly, health friendly…

I fondly hope and fervently pray (Lincoln’s words) that the next Swamy will be Farmer-Friendly!

- Vinay Hardikar

vinay.freedom@gmail.com

(The writer has been working in the public sphere of Maharashtra for the last five decades. His versatile personality has several dimensions, but the primary ones remain to be that of an established writer, journalist, editor, critic, activist, and teacher.)

तात्कालिक घटनांच्या संदर्भातून शेतीच्या मूलभूत समस्यांची ललित भाषाशैलीने पुनर्मांडणी करणारे पुस्तक :

Tags: m s swaminathan swaminathan ayog agro economist obituary agrarian crisis manmohan singh shetkari sanghtana sharad joshi vinay hardikar Load More Tags

Add Comment